- HubPages»

- Travel and Places»

- Visiting North America»

- United States»

- Arizona

Fray Marcos de Niza and His Monument

A Saturday Afternoon Drive in the Country

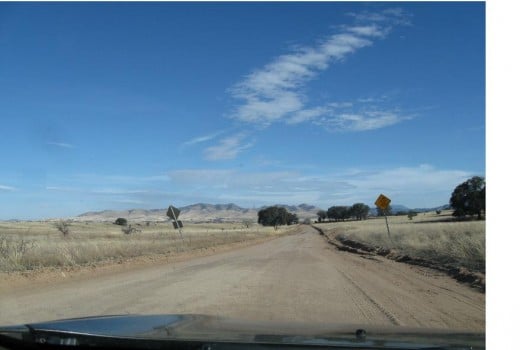

Driving south on Duquesne Rd in the Santa Cruz County sector of the Coronado National Forest in Southern Arizona one comes upon a broad, grassy plain which looks more like it belongs in the grasslands of the Great Plains rather than in the mountains of Southern Arizona.

While the mountains form a backdrop in the distance, the area between the mountains on the sunny March day that we visited area was mostly brown grass dotted with the occasional trees, windmills and small patches of green where water was obviously present near the surface.

We had spent the last hour or so leisurely traversing our way through the mountains of this area while driving along a dirt road of varying quality.

While known as the San Raphael Valley, this area is really a high, mostly flat, plateau that happens to be surrounded by even higher mountains thereby allowing it to meet the definition of a valley.

While still dirt, this section of the dirt road we had been traveling on was straight and hard packed giving it the feeling of being almost paved.

Time to Stop and Take Some Pictures

We had been driving for almost two hours and appeared to had covered over twenty of the twenty-three to twenty-five miles that the signs claimed to be the distance from our starting point in the little Southern Arizona city of Patagonia and the border ghost town of Lochiel, Arizona, when I spotted a windmill in an open field and decided it was time to stop for a picture.

After photographing the windmill, the large sycamore tree next to it and a small patch of green in the meadow with a broken down fence and what appeared to be two grave markers I suddenly remembered that, in addition to ghost towns, I was also looking for a monument to an explorer named Fray Marcos de Niza.

The short paragraph that I had seen which recommended this ghost town side trip while visiting Patagonia, had said that a landmark for the monument, which would be on the right side of the road when traveling south, would be a large sycamore tree on the left.

Glancing twenty yards or so down the right side of the road, I noticed what appeared to be the top of a cement cross sticking up above a small rise in the terrain.

Coronado National Forest

I First Learn of Fray Marcos de Niza

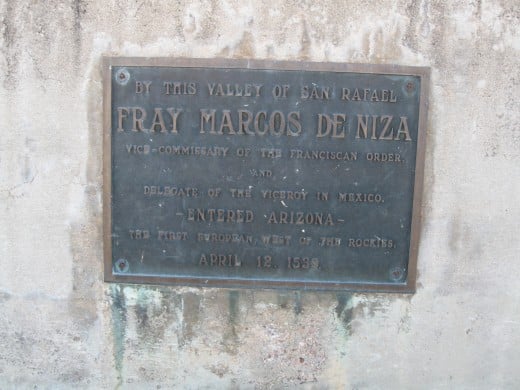

It was a beautiful Saturday in Spring when my wife and I decided to go out and spend the day enjoying the little Santa Cruz County town of Patagonia and surrounding area. I had never heard of Fray Marcos de Niza before doing a quick Google search on Patagonia, Arizona to get an idea of what to see in the area. Quick is an understatement as my wife was literally dragging me out of the house so we could be on our way - she had no time for trip planning. However, the one sentence that mentioned the monument also included the statement that de Niza was the first European to set foot in what is now the United States west of the Rocky Mountains. This also made him the first European to set foot in Arizona as well.

Given that the monument was located in the middle of nowhere, I expected it to be a metal plaque attached to a rock that was more than likely overgrown with grass. The fact that the author of the site suggesting the tour had felt the need to mention the sycamore tree as a reference point simply reinforced this. However, there was no need to use the sycamore as a reference point and the monument itself stands out prominently on the landscape. The metal plaque is mounted on a massive concrete monument.

Frequently, what I do after discovering a roadside historical marker or hear of a local or regional historical story that piques my interest, is to check it out on the Internet with a Google search. For some topics, like my Hub The Lady in Blue, which was about the seventeenth century Spanish Nun, Maria Agreda, who not only, while in deep mystical trances felt she had been transported to the American southwest where she preached to the Indians, but whom numerous Indians when they first encountered Spanish explorers and missionaries displayed a knowledge of the Catholic faith and were able to describe Maria Agreda in detail I found an abundance of good information with a few searches. While others, like my Hub on Mathew Juan the first Arizonan and first Native American killed in World War I, took an entire three day weekend to gather enough solid information to provide an accurate account of him and his deeds in the war.

The Journal of Fray Marcos de Niza

de Niza's Monument on the Plain

Fray Marcos de Niza and His Life

De Niza was born around the year 1500 in either France or Italy. He spent his youth in Nice which was then a part of the Duchy of Savoy and, upon becoming an adult, he entered the Franciscan order which sent him to Santo Domingo (present day Dominican Republic) as a missionary. Following his assignment in Santo Domingo he received other missionary assignments to Guatemala, Peru and finally Mexico City.

In 1536 Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca and three companions arrived in Mexico City and recounted their harrowing eight year experience wandering through the new lands to the north of Mexico and Cuba.

Cabeza de Vaca and his three companions were the lone survivors of the Narváez expedition which had began in 1527 when Pánfilo de Narváez, Spanish Governor of Florida, armed with a commission from King Charles V of Spain, set out to explore and establish two colonies along the Gulf Coast of what is now the United States.

Hurricanes, fights with the native Indians and disease took the lives of all but Cabeza de Vaca and his three companions who were then forced to make their way on foot from the Texas Gulf coast to Mexico.

Cabeza de Vaca and his companions were the first Europeans to explore present day Texas and possibly parts of New Mexico and Arizona. Unlike de Niza whose later expedition made it back intact to Mexico City and who also kept a very good written account of his travels, Cabeza de Vaca and his men were forced to simply wander and live off the land with only their memories to record what they had seen.

Upon hearing Cabeza de Vaca's account of their travels, and believing that great riches were to be found in the areas north of Mexico, the Spanish Viceroy Antonio de Mendoza put together plans for an expedition to be led by Francisco Vásquez de Coronado to explore the area and find the riches.

The Viceroy had de Niza undertake a preliminary exploration of the area in 1539 a year before Coronado was to undertake the major expedition. The preliminary expedition led by de Niza left Mexico City and, according to the detailed journal that de Niza kept, arrived in what is now Arizona on April 12, 1539. The monument to de Niza sits about a mile north of one of the possible points where de Niza appears to have crossed the present day border and entered Arizona.

Included in de Niza's party was a man named Estabanico or Estevan the Moor a former Moorish slave who had been one of the three men who had survived the Narváez expedition with Cabeza de Vaca.

Taking advantage of Estabanico'sprevious travels, de Niza sent him ahead to seek out the wealth they were looking for. Estabanico got as far as the Zuni Indian Pueblo of Hawikuh, in what is now western New Mexico, before being killed in a battle with indians.

Upon receiving word of Estabanicos death, de Niza and the Mexican Indians in his party headed north toward Hawikuh with caution. Rather than risk contact with the local Indians and possibly meet the same fate as Estabanico, de Niza elected to simply observe Hawikuh from a distant hill. Unfortunately the distance and the angle of the rays of the brilliant desert sun caused the buildings in Hawikuh to appear to have been made of gold. Thinking he had found the gold he was looking for, de Niza headed back to Mexico to report his find.

Upon receiving de Niza's report of a city made of gold, the Spanish Viceroy gave Coronado permission to proceed with his expidition. Fray Marcos de Niza accompanied Coronado as planned.

However, when Coronado's force captured Hawikuh in July of 1540 and the troops saw that the buildings were not made of gold but of mud and straw with no gold in sight their anger toward de Niza reached murderous proportions.

Rather than risk de Niza being harmed or killed by the troops, Coronado elected to send him back to Mexico in disgrace while the expedition itself searched all the way to modern Kansas in their attempts to find gold.

Because of his extensive journals and notes from his 1539 journey Fray Marcos de Niza is remembered today. However, following his fall from grace, de Niza appears to have retreated into the monastic life ultimately ending his days in a monastery at Xochimilco outside of Mexico City. It was here he died on March 25, 1558.

Two Views of the Monument

The Monument

Unlike most historical markers and stone monuments, there is nothing on the de Niza monument to indicate when it was put up or what group was responsible for errecting it. There is also the question as to why whoever was responsible for building the monument selected a spot along a little used dirt road in the wilderness area of a National Forest almost thirty miles from the nearest town. Since the site is almost a mile north of the international border, it does not mark the exact spot where de Niza probably entered Arizona.

Looking at the monument (and this can be seen in my pictures) it is easy to see that it has a definite structure and is not simply a plaque on a stone marking a particular spot. Instead, the monument is in the form of a small outdoor chapel, with concrete bench seating along each side, raised altar under the cross in front and a concrete floor with room for a fair number of people to stand or, if they brought folding chairs, sit within the center of the structure. A Mass could be celebrated here, assuming enough people were willing to undertake the hour drive over the primitive road.

Finding information about de Niza on the Internet was easy, as was finding pictures (note: all of the pictures on this Hub were taken by me, however, there are hundreds of photos of the monument and plaque that have been taken and posted by others on various Internet sites), descriptions of the monument and directions for getting there. But practically nothing about when it was built, who was responsible for it being built and why this particular location was selected.

After much searching, I came across a copy of an appendix to a report published by Tucson's Center for Desert Archeology which listed the de Niza monument along with a number of buildings and other structures in Tucson and southern Arizona which the author's felt should be included in the National Register of Historic Places. The brief write up stated that the monument had been built by the National Youth Administration (which was a part of the New Deal era Works Progress Administration better known as the WPA) in 1939 for the 400th Anniversary of de Niza's entry into Arizona. It also indicated that the de Niza monument was associated with the creation of the Coronado National Memorial park area which sits on the Mexican border and is twenty some miles southeast of the de Niza monument.

Both the de Niza and Coronado projects appear to have started separately and both appear to have been initially initiated by business and civic boosters interested in preserving their cultural heritage. Of course this was the time of the Great Depression of the 1930s when the Federal Government was heavily involved in building projects, including park and monument building, as a part of its stimulus spending programs.

The Coronado Memorial project was the bigger of the two projects both with more people involved in its organization and more support in Washington and the capitals of Arizona and New Mexico while the de Niza project was smaller and centered in Arizona only.

The cities of Nogales and Bisbee were both lobbying to land either or both the Coronado Memorial and de Niza Memorial. Both of them failed to get either project.

Also, at that time, there was some population in the area where the de Niza monument is located. In addition to ranchers, some of whom are still there, there were at least two towns, Lochiel and Washington Camp, with people living in them as well as Harshaw, Mowry and Duquesne which may also have had some people living in them. All were in decline and all are ghost towns today.

It is possible that when Congress passed legislation creating the Coronado National Memorial further east in Cochise County, that officials in the city of Nogales (which lay 40 miles due west of the Coronado Memorial but 80 miles away by existing roads) may have decided to throw their support behind the present site for the de Niza monument for two reasons.

First, it was obvious that Nogales and Bisbee were in a stalemate over the site with each strong enough to block the other from getting the monument but not strong enough to land it themselves.

Second, by locating the monument to the west between the Coronado Memorial and Nogales (Bisbee is east of the Coronado Memorial) Nogales may have hopped to be able to pull future development of the Coronado Memorial (the original plans for the Coronado Memorial were for a large International Park covering miles on both sides of the border but poor relations with Mexico and budget problems killed that idea) toward Nogales. There was also talk of the possibility of a highway being built between Nogales and the Coronado Memorial and having the de Niza Monument by Lochiel would help to justify such a road. Lochiel, of course would benefit economically from such a road as well so their officials would have pushed for the current location of the monument.

However, with World War II fast approaching the road idea was dropped. Lochiel continued to decline economically to the point where today the border crossing has been sealed off and the town a ghost town with zero population. A dirt road still crosses the mountain and connects Nogales with the road on which the de Niza monument is located but the climb over the mountain makes this road even rougher than the road from Patagonia to the monument and there is no direct road of any type between the monument and the Coronado Memorial which leaves de Niza's monument sitting alone and rarely visited in the middle of the high desert plain.

Views of the de Niza Monument

Links for Additional Reading on Fray Marcos de Nazia

- The Mysterious Journey of Friar Marcos de Niza

More detailed information on Fray Marcos de Niza and his travels in what is now the United States. - The Story of the Coronado Memorial

A 420 page history of the creation of the Coronado Memorial. Also included is a discussion on the creation of the de Niza monument and its link to the memorial. - National Youth Administration - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Information about Depression Era National Youth Organization.

The Border Today