- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era»

- Twentieth Century History

History of Military Conscription in the United States

U.S. Government Resorted to Military Conscription 4 Times in History

World War I was the second time in history that military conscription or a draft was used by the U.S. Government to fill the ranks of military forces.

A military draft was used by both the Union and Confederate governments during the Civil War to help fill the manpower needs of their regular armies. The draft was also used by the U.S. Government during World War I, World War II and from 1948 to 1973 during the Cold War.

Historically, the United States has always favored a small standing national military. For national defense the United states has historically relied on the individual states to maintain a corps of trained citizen soldiers ready to take up arms and come to the nation’s defense.

Citizen Soldiers and America's Dual Military System

From the end of the American Revolution to the present, the United States has always been quick to shrink the active armed forces as soon as a war ends. America's Founding Fathers were concerned about entrusting the Federal government with a large standing military in peacetime.

Instead, we as a nation have preferred to rely on a small standing national military augmented with part-time citizen soldiers under the peacetime control of the individual states.

This tradition goes back to Colonial times each when each colony, and later each state, maintained their own militia (now known as the National Guard) which, except in times of national emergency, have been under the control of the individual states and territories (Guam, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands all have their own National Guard units).

National Guard units are organized and managed by their respective states with each state’s governor being the commander-in-chief of the state’s National Guard. In times of war or national emergency the Constitution gives the President the power activate and take command of a state’s National Guard and deploy it with the nation’s regular military forces.

Militia or National Guard units have been activated and played an active fighting role alongside regular troops in practically every war from the French and Indian Wars of the Colonial period through the current War on Terror.

Massachusetts Colony Conscripted Men in 1636 to Defend against Pequot Indians

Military Conscription in American History

The American militia tradition began in 1636 when the governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony organized three companies of militia to defend the colony against the neighboring Pequot Indians. Each company was led by a lieutenant colonel appointed by the governor with lower ranking officers being elected by the men in each company. The governor was the commander-in-chief.

To fill the ranks of the new militia, the governor’s order required all males in the colony between the ages of 16 and 60 to own a gun and be ready to fight in the defense of the colony. This is the first instance of conscription being used in what is now the United States. These first conscripts were not only required to fight but were also required to provide their own weapons.

Other colonies soon followed suit by forming militia to defend against Indian attacks in frontier areas as well as, during the French and Indian Wars, against attacks by the French and their Indian allies. In some areas militia membership was voluntary while in others men were required by law to train and fight with the militia.

During the American Revolution much of the fighting was done by militia with many of the members being conscripted into their colony’s militia for service against the British.

The Second Continental Congress, our national governing body during the Revolutionary War, made requests to the colonies to help fill the ranks of the Continental Army (the national army) by conscripting and sending the men to serve directly in that Army. Few colonies came through with recruits for the Continental Army.

Following the American Revolution members of Congress, from the Administration of George Washington’s to the start of the Civil War, continually refused presidential requests to pass a draft law.

Each of the four times the draft was used, Congress passed a separate draft law that was allowed to expire at the end of each of these wars.

The Cold War draft law was passed in 1948 and continued until 1973 when, in the wake of anti-draft protests during the Vietnam War, new legislation was passed which, while keeping the Selective Service System which managed the conscription process, ended the registration and drafting of men for military service. A 1980 Executive Order issued by President Jimmy Carter reinstated the Selective Service registration requirement but not the draft.

The World War I Draft

World War I began in Europe in 1914 but the United States did not declare war until 1917.

Prior to the start of the war some of the combatant nations such as Germany, Russia, Turkey, France and Austria-Hungary, were already using conscription to fill the ranks of their military forces. Other nations, mainly Great Britain and the British Commonwealth nations, had volunteer armies at the start of the war but low numbers of volunteers forced these nations to implement a draft during the war.

By the time the United States entered the war all of the countries already involved in the war were using conscription to fill the ranks of their military forces.

The United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917. However, preparations for war began earlier with the National Defense Act of 1916 which authorized the expansion of the U.S. Army from around 100,000 men to 165,000 men and the National Guard from around 115,000 men to 450,000 by 1921.

Following the declaration of war, President Wilson sought to increase the U.S. Army (which by that time had increased to 121,000 and the National Guard increasing to 181,000) to one million men. However, within six weeks of declaring war only about 73,000 men had taken up the call and voluntarily joined the army.

With enlistments not increasing as hoped for, Congress, on May 18, 1917, enacted the Selective Service Act of 1917 which called for the registering of all men for military service.

Three such registrations occurred during World War I. The first was on June 5, 1917 which required all men between the ages of 21 and 31 to register for military service. The second registration took place on June 5, 1918 for men who had reached age 21 after June 5, 1917. This second registration was supplemented by a follow-up registration on August 24, 1918 for those who turned 21 after June 5, 1918.

The third registration was held on September 12, 1918 and this one expanded the age range to all men age 18 through 45.

My Great-Uncle Walt a WW I Draftee

Universal Registration but Selective Conscription

Registering for the draft did not mean that a man would automatically be placed in the military. This was a selective system which sought able bodied men who were both fit to fight and not needed elsewhere for the war effort.

There were five classes into which those who registered were placed:

-

Class 1 - those slated for military service

-

Class 2 - men considered by their local draft board to have skills necessary for an agricultural or industrial enterprise whose production was critical for the war effort. This class also included registrants who were married and had children or were fathers of children whose mother was deceased.

-

Class 3 - necessary assistants, associates or managers in industrial enterprises critical to the war effort as well as county and municipal officials, custom house clerks, mailmen, police and firemen. Also included were men who provided sole support for children that were not their own or had parents or grandparents who depended upon them for their support.

-

Class 4 - registrants who were the sole managing, directing or controlling head of an organization critical to the war effort. Seamen involved in commercial shipping were also included in this class.

-

Class 5 - Federal and State officials, licensed pilots employed in aviation, clergymen and seminary students, people in miscellaneous industries and professions deemed critical to the war effort, resident aliens (foreign citizens not intending to become U.S. citizens), enemy aliens (these were probably German and other citizen or subjects of nations at war with the Allies who were not members of diplomatic missions but tourists, employees of foreign companies, etc. who happened to be in the U.S. when war was declared), men who were physically or mentally unfit for military service, men in prison, men in insane asylums and most American Indians.

In most cases, all registrants were initially placed in Class 1 and, after their cases were reviewed, either remained in Class 1 or moved to another class. While Federal law and regulation guided the system, it was local draft boards, made up of citizen volunteers, that handled the actual registration and classification.

Class 5 was the only class in which those in it were exempt from the draft. Those in the other four classes were subject to being drafted but, before drafting men from Class 2 the local board had to have drafted everyone in Class 1 and the same for Classes 3 and 4. The lower one’s class was on the list the greater the chances of NOT being drafted.

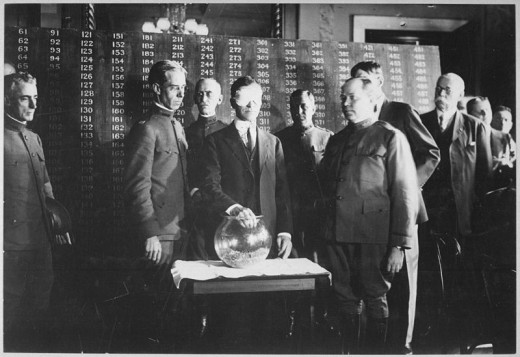

Even for those in Class 1, being put in that class did not mean that they would be drafted immediately as the call up was according to where an individual’s registration number was in the draft lottery which had been held on July 20, 1917 in Washington, D.C.

First Draft Number Being Drawing on July 20, 1917

American Indians and the World War I Draft

While estimates vary as to how many American Indians served in the military during World War I, many American Indians did voluntarily enlist and serve in the armed forces of the United States in that war. This despite the fact that the law automatically placed most American Indians in Class 5 thereby exempting them from being drafted.

Prior to the Indian Citizenship act of 1924 few American Indians were considered American citizens. Some late 19th century laws as well as intermarriage with white settlers did enable a some American Indians to have American citizenship.

Like other males in the United States in 1917, all American Indians were required to register for the draft but, according to the 1917 Selective Service law, only those who were American citizens or residents seeking citizenship were eligible to be drafted.

Despite the fact that most were not subject to the draft, many American Indians quickly volunteered for military service. In fact the Onondaga and Oneida Indian nations in New York State actually issued their own declarations of war against Germany and informed President Wilson that their men were ready to join and fight in the U.S. Army.

Also, while the law may have been clear with regard to the fact that the majority of American Indians were non-citizens and therefore were not to be drafted, this fact was lost on many government officials involved with operating and enforcing the draft at the local level.

It also didn’t stop many overzealous citizen mobs, fired up in part by the Federal Government’s pro-war propaganda machine, who took it upon themselves to round up and deliver to recruiters so called draft slackers or men, including American Indians, who were or even appeared to be evading the draft and military duty.

American Indian leaders differed on how to deal with the draft. Many opposed requiring American Indians to register for the draft because, as non-citizens, Indians were not allowed to vote. Other leaders wanted to use draft registration and military service as leverage for granting American Indians full citizenship rights.

My Uncle Walt & Other 309th Field Artillery Band Members in Barracks at Ft. Dix, NJ

Economics of Conscription

The stated reason given for the need by the United States, and other nations, to resort to conscription during World War I was a shortage of manpower for the military.

As first year year economics students quickly learn, shortages in any type of market, including labor markets, are the result of an imbalance between supply and demand. Whenever, price (or wages in the case of labor) is set below market equilibrium shortages follow.

The shortage could have been eliminated by increasing wages as this would have induced more men to enlist. It also would have forced the government to use military recruits more efficiently thereby reducing the numbers needed as only about half of the military personnel ended up being assigned to the European Theater of War which was the focus of the main fighting.

Also, when a war has popular support more men (and nowadays women) are willing to accept less than a market wage in exchange for the opportunity to serve their country. Thus, while an all volunteer force would have been more expensive to recruit, the willingness of many to join at a below market wage (but greater than the conscription wage) plus the more efficient use of recruits would have made the total military manpower cost less than the going market wage times the 4.7 million men that were ultimately pulled into military service.

Conscription Shifts Major Part of Cost of Defense to those Drafted

Conscription results in shifting much of the labor costs of military defense from taxpayers to the conscripts as they end up bearing a sizable portion of that cost in the form of lost market wages.

In addition, the burden is uneven in that the financial sacrifice is greater on some (those with families to support, careers or businesses that are harmed by their leaving, etc.) while others for whom the financial sacrifice would be less end up not being called due to the random nature of the selection process. There is also the petty corruption in which those with connections are able to get moved to a lower draft class thereby avoiding being drafted.

Despite the unequal sacrifice and lukewarm enthusiasm for the war by many average citizens and their families, most men not only complied with the law but, when called, served valiantly and gave their all including their lives for their country.

Barracks at Ft. Dix, NJ 1917

Returning World War I Vets Feel They Should Be Compensated for Their Sacrifice

According to government data a total of 4.7 million men served in the American military during World War I. A little over 2 million were sent to the the European Theater of war (most served in rear areas and not in actual combat) with the remainder serving within the the U.S. proper and in American territories in the Caribbean and Pacific.

Of the 4.7 million who served, 4.4 million returned alive and physically unharmed. 204,000 of those who returned had received non-lethal wounds - these ranged from minor to physically disabling. 53,402 died serving in the European Theater of War. Most of these were combat related with the rest being disease and accidents, while an additional 63,114 died of disease and accidents outside of the European Theater of War.

While the vast majority of veterans returned home alive and physically unharmed, many of these men and their families resented the financial and other sacrifices they had made on behalf of the war effort. Even those who had never left the United States had been forced to put their life on hold with their daily routines being dictated by military superiors. Some had suffered from the Spanish Flu epidemic, which swept through military camps in the U.S. and Europe, and had seen buddies die of this.

Many veterans, their families and friends began pushing for compensation for the sacrifices all veterans had made. Both the Federal and state governments were pressured to provide compensation to veterans. The Federal government had started providing limited medical and some vocational training services to wounded veterans as some compensation to wives and families of those who gave their lives in the war.

Some state and local governments began offering some limited services to veterans especially those who were wounded or unemployed. These included things like veteran preferences government jobs, some job training and placement assistance and credits for veterans that allowed them to reduce their property taxes.

These were minimal and varied by state which caused the veterans to focus efforts on the Federal government which had been responsible for drafting them.

WW I Veterans Bonus and Expansion of Veteran Benefits

In 1924 Congress finally passed, over the President’s veto, the World War Compensation Adjustment Act, which provided a bonus paid to veterans based upon their length and type of service performed during the war.

Those receiving small bonuses, i.e., $50 or less, received cash while the remaining 3,662,374 veterans received military service certificates entitling them to a bonus payment 20 years hence.

The legislation created a trust fund into which the Federal government, beginning in 1925, would contribute $112,000 per year for 20 years. The contributions plus the interest earned would add up to the $3.368 Billion needed to redeem the military service certificates in 1945.

With the country in the midst of a recession in 1924 many out of work veterans and their families needed the money then and not in 20 years.

The 1923-24 recession ended but agitation for the bonus continued.

In the spring of 1932 the nation was in the midst of the more severe Great Depression of the 1930s. A small group of out of work veterans undertook a march on Washington to press for early payment of the bonus. While their pleas fell on deaf ears many other unemployed veterans saw what was happening and made their way to Washington, some with wives and children in tow, to join the protest.

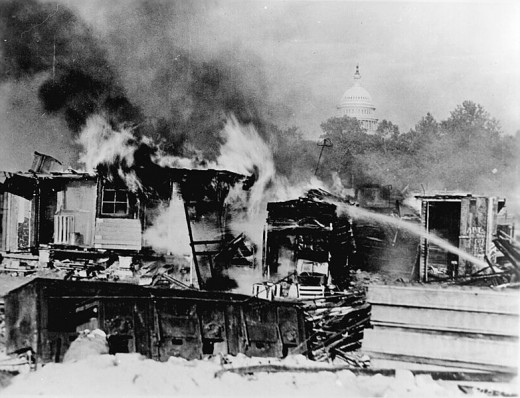

By the summer of 1932 the numbers of unemployed veterans and families came to somewhere between 15,000 and 40,000 (estimates vary depending upon the source and their political agendas). These Bonus Expeditionary Forces as they had come to be called were living in squatter camps (called Hoovervilles after President Hoover who opposed early payment of the bonus) outside Washington that were becoming a public health hazard due to the squalid conditions in the camps.

Realizing that something had to be done, President Hoover ordered Army Chief of Staff, General Douglas MacArthur, to use U.S. Army troops to clear the camps. This was a public relations disaster along with injuries on both sides - however, not shots were fired and no one was killed.

The bonus marchers were forced to return home and the Federal Government ended up paying a total of $76,212.02 to some 5,000 of the marchers, who were broke and far from home, to pay for transportation home plus 75 cents per day for food while traveling.

Agitation continued at both the state and Federal level for early payment of the bonus. President Roosevelt (whose election had been helped by the negative publicity surrounding President Hoover’s ordering troops to evict the marchers from Washington) tried, with limited success, to pacify unemployed veterans by offering them jobs in his Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC).

Finally in 1936 Congress passed legislation over President Roosevelt’s veto (like his predecessors, Roosevelt opposed early payment) authorizing the VA to certify and begin redeeming the 1924 military service certificates at face value.

Bonus Army Shacks on Anacostia flats in Washington, DC Buring

Legacy of World War I Draft

In the years since the end of World War I and the demobilization of the troops the government has spent billions of dollars dealing with and compensating veterans and their families for the war that the Wilson Administration tried to fight on the cheap using military conscription.

Despite the fact that World War I ended a little over 96 years ago and the last American veteran of that war, Frank Buckles, died in 2011, the U.S. Government still spends some $20 Million per year on disability payments to 3,431 widows and disabled adult children of World War I veterans. While decreasing, these payments will continue years into to the future as most, if not all, of the children and many of the widows were born years after the end of the war as many veterans married younger women either late in life or following the death of their first wife late in life. Many of these late in life marriages produced children who are alive today.

Efforts by World War I veterans and veterans groups led to changes in the way all veterans were treated and this helped veterans of World War II and subsequent wars to avoid many of the hardships encountered by World War I veterans.

However, like conscription itself, the has and, in many cases, continues to be random in that it helps some but misses others either died or lost everything before receiving the needed help and compensation.

It has also resulted in the development of bloated and inefficient bureaucracy, the Veterans Administration, whose rules and processes are so complex that results in not knowing what they are entitled to or, if they do, are unable to navigate the complex sea of paper needed to receive benefits.

The process of caring for and helping those who have fought for our freedom now costs about $1.3 Trillion dollars per year and growing. According to some the costs of providing promised services to veterans will soon eclipse those of the financially ailing Social Security and Medicare programs.

© 2015 Chuck Nugent