- HubPages»

- Education and Science»

- History & Archaeology»

- History of the Modern Era»

- Twentieth Century History

U S Navy NC-4 - First Plane to Fly Across the Atlantic Ocean

Air Race With British at Start of 20th Century Similar to Space Race with Soviets in Mid Century

It has been 46 years, almost a half a century since the Russian Cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first person to cut the bonds of Earth and venture into space on April 12, 1961. A mere four years earlier, on October 26, 1957, the Russians had launched the world's first artificial satellite thereby ushering in the Space Age and launching the great space race between the Soviet Union and the United States.

While the space race played a prominent role in the last half of the 20th century, the predecessor to the Space Age, the Air Age, was a dominant feature of the early decades of the century. Following the first successful powered flight by the Wright brothers at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina on December 17, 1903, the Air Age was launched and aircraft technology began advancing at a rapid pace with new distance records being set regularly. The start of World War I resulted in governments becoming heavily involved in advancing aircraft technology as planes soon became important elements in the war effort. One thing that the military was not able to accomplish during the war, despite trying, was to transport war material across the Atlantic on airplanes. The Germans' use of submarines to blockade Britain and France gave them a significant advantage that resulted in the loss of critical war material due to cargo ships being sunk by German submarines. Cargo aircraft would have nullified this advantage as submarines posed no threat to airplanes.

A U.S. Navy Flying Boat Becomes First to Fly from North America to Europe

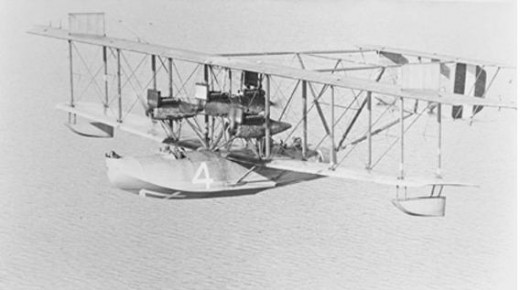

In 1914 a plane, actually a flying boat, had been designed by Glenn Curtiss and financed by Rodman Wanamaker, the Philadelphia philanthropist and son of department store magnate, John Wanamaker, with the intent of flying it across the Atlantic. But the war in Europe intervened and the plane ended up being sold to the British Navy for submarine patrol duty. With the U.S. entry into World War I, the Navy contracted with Curtiss to design and build more of these flying boats which came to be known as Nancies as their military designation was NC (for Navy-Curtiss) followed by a number.

With the war over, the race to be the first to fly cross the Atlantic resumed in earnest. Since the British Navy was looking to fly one of their sea planes across the Atlantic and the London newspaper, the Daily Mail, had offered a prize of £10,000 for the first plane to fly non-stop across the Atlantic, the U.S. Navy, feeling that U.S. honor was at stake, committed itself to having one of their Nancies be the first to fly across the Atlantic.

Rather than attempting the 1,900 nautical mile flight from Newfoundland to Ireland, the U.S. Navy elected to take the shorter 1,200 nautical mile leg from Newfoundland to the Azores, then fly from the Azores to Europe and on to their final destination which was in England. Thus, the American objective was to simply be the first to fly a plane across the Atlantic Ocean rather than fly non-stop across the Atlantic. In the past, planes manufactured in the U.S. had been delivered to Europe by boat. As a result of the refueling stop in the Azores, the American flight would not qualify for the £10,000 prize offered by the Daily Mail, but then, why would a government entity be concerned about a £10,000 prize when they could always hit up the taxpayers whenever they needed money?

Unlike the individuals competing for the prize money and trying to maximize their profit by keeping costs well below the coveted prize amount, the U.S. Navy threw all of its resources into this project. To increase the odds of making the flight across the Atlantic, not one, but three Navy-Curtiss flying boats were to make the trip. These three constituted their entire stock of operational Navy-Curtiss flying boats. Naval ships were deployed all along the route to assist with navigation and rescue if needed. In effect this was a dress rehearsal for the manned space flights later in the century. Like, the first manned space flights in the 1960s, this first trans Atlantic flight in 1919 was a leap into the unknown.

On May 8, 1919 the three Navy-Curtiss flying boats, the NC-1 commanded by Patrick N.L. Bellinger, the NC-3 commanded by John H. Towers (who was also the expedition commander) and NC-4 commanded by Albert C. Read, took off from the Rockaway Beach Naval Air Station on Long Island bound for Halifax, Nova Scotia. The NC-1 and NC- 3 completed the first leg without problem but the NC-4 had engine trouble and was forced to land off of Cape Cod for repairs. If it hadn't been for some weather and other problems in Halifax, the NC-1 and NC -3 would have left without waiting for the NC-4 as others competing for the £10,000 Daily Mail prize were already in Newfoundland making final preparations for their flights to Ireland. In fact, a little over a month after the U.S. Navy Nancies left Newfoundland the British team of Alcot and Brown succeeded in making the non-stop flight from Newfoundland to Ireland.

As it was, all three planes left Nova Scotia together and headed for Newfoundland and then the Azores. Fog and other problems not only made the flying difficult and ultimately resulted in both the NC-1 and NC-3 being forced to land in the middle of the ocean, leaving the NC-4, whose problems at the start of the flight had almost forced her out of the project, as the only one to reach the Azores by flying. NC-1 battled heavy waves and stayed afloat long enough for the crew to be rescued by a passing Greek freighter while John H. Towers and his crew managed to sail the NC-3 over 200 miles to the Azores. NC-3 had made it to the Azores under her own power but part of that trip had been as a boat rather than as an airplane. The NC-4, the only plane in the party that had actually flown to the Azores and still in flying condition, was forced to leave the Azores alone.

Like the space race a half century later, the flight of the Nancies was front page news and eagerly followed by readers in the U.S. and Europe. When news reached Newfoundland that the NC-4 had landed at Horta, in the Azores, thereby completing the longest leg of the journey, the British flyers, making final preparations for their flights attempting to win the £10,000 prize, became very concerned. Even though the U.S. Navy planes were never a threat in terms of the prize money, national pride kicked in and the British fliers couldn't bear the thought of Americans making the first successful flight across the Atlantic before the British even if the Americans did stop en route. With three sets of British pilots (while all were current or former military pilots, they were doing this as private citizens and not as part of the military as were the U.S. pilots) each vying against the others for the £10,000 prize there was pressure enough for each one to take off as soon as possible. But now, there was added pressure in that both national honor and the personal glory of the ultimate British winner of the prize would be diminished if the American NC-4 reached the European continent first.

Rushing, the first team consisting of Hawker and Mackenzie-Grieve took off from Newfoundland for Ireland on May 18th. Following them about an hour later was the team of Raynham and Morgan whose plane proved to be too heavy for the soggy field which they took off from resulting in their crashing on take off. Hawker and Mackenzie-Grieve didn't have much better luck as their plane ran out of fuel halfway between Newfoundland and Ireland forcing them to ditch into the sea. However, news of the flights leaving Newfoundland now put the pressure on Read and his crew as weather and engine problems forced them to remain in the Azores.

Finally on May 20th the NC-4 was able to leave Horta and make the 150 nautical mile flight to Ponta Delgada in the eastern Azores. More problems forced the NC-4 to delay their departure from Ponta Delgada until May 27th. During this time they received news that that Hawker and Mackenzie-Grieve had been rescued by a Danish tramp steamer and had been safely deposited them in Scotland where the ship docked. Alcot and Brown were still in Newfoundland but, as their plane was not yet ready they were not an immediate threat. Still in the running to be the first to cross the Atlantic, Read and his crew finally began their 800 nautical mile flight to Lisbon, Portugal early on the morning of May 27th. Again there was a line of American Navy ships that stretched along the route from the Azores to Portugal both to assist them with navigation and to report their progress. As dusk began to fall they spotted the light from the Cabo de Roca lighthouse located on the westernmost point of Europe. As they flew over the lighthouse en route to Lisbon, Europe lay beneath them. While their flight plan called for a stop in Lisbon and then a final 755 nautical mile leg to Portsmith, England, the goal of their mission had been accomplished as they had become the first to fly a plane across the Atlantic Ocean.

Three days later, on May 31, 1919 the NC-4 landed in Portsmith, England, ending a trip that had started 24 days and almost 4,000 nautical miles earlier in Rockaway Beach, Long Island.

Two and a half weeks later, on June 18th, Alcot and Brown rushed out of Newfoundland with new competitors close behind and, eighteen hours later crash landed in a field in Ireland thereby becoming the first to fly non-stop across the Atlantic Ocean and collecting the £10,000 prize from the Daily Mail. While Read and his crew made the first flight across the Atlantic, they had to make use of the Azores, which lie between North America and Europe, as a refueling stop. Alcot and Brown soon followed with the longer flight non-stop from the eastern most large island, Newfoundland, off the coast of North America to the western most large island, Ireland, off the coast of Europe. However, eight years later 1927, in a quest for a new prize, the American aviator, Charles Lindbergh, flew non-stop from New York City on the North American mainland to Paris on the European mainland, bypassing all the islands in between. Thanks to these brave pioneers, and their fellow aviators who were not as lucky, the Atlantic Ocean, once a great barrier and now affectionately referred to as the pond by the British, is crossed daily by thousands of people in our sleek, modern, passenger jets.