What Makes Komodo Dragons Deadly? Is It True Komodo Dragons Can Develop From Unfertilized Egg Cells?

What are Komodo Dragons

September 27, 2009

While Komodo Dragons have been around for millions of years, they have been little known beyond the few remote islands in the Indonesian Archipelago where they exist. It wasn't until 1910 that their existence was confirmed, thanks to a successful hunt that resulted in photographs and a skin, by Europeans.

Two years later, in 1912, the first western scientific paper dealing with Komodo Dragons was published thereby making the existence of the Komodo Dragon known to the outside world.

However, the remote location of the Komodo Dragon's habitat, the two World Wars of the Twentieth Century and politics all combined to limit study of these creatures.

However, this is changing as more of the world's major zoos have Komodo Dragons to exhibit, as the protected habitat of the Komodo Dragon has become more accessible to tourists and as more scientists and naturalists have had access to study these creatures.

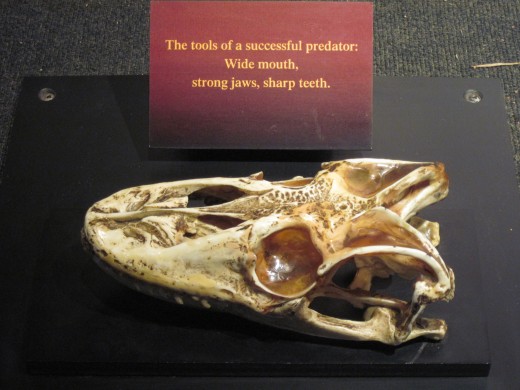

Given its size, powerful jaws and ability to attack a prey quickly from ambush, the Komodo Dragon can hold its own in the wild. While the Komodo Dragon is capable of overtaking and killing other animals for food based upon its strength and agility alone, a few additional weapons in its arsenal.

Komodo Dragon Hunting Habits - the Conventional Theory

Conventional wisdom has it that, in addition to its other strengths, the saliva in the Komodo Dragon's mouth is alive with numerous varieties of deadly bacteria. While these bacteria cause no harm to the Komodo Dragon, the toxins they release as byproducts of their daily activities are deadly when they enter the bloodstream of creatures bitten by a Komodo Dragon. Thus, an animal that has been attacked and bitten by a Komodo Dragon but manages to escape the clutches of the Komodo will generally die within a day or two.

Many die through the simple loss of blood from the wound created by the bite. However, even if the bleeding is not severe enough to kill the animal, the bacteria laden saliva that enter the wounded victim's body as a result of being bitten will usually result in death within a day or two as the bacteria in the Komodo Dragon's saliva mixes with the victim's blood and is distributed through its body by the blood. The wounded animal is soon poisoned as the bacteria reproduce and multiply while releasing toxic poisons as a by-product of their existence.

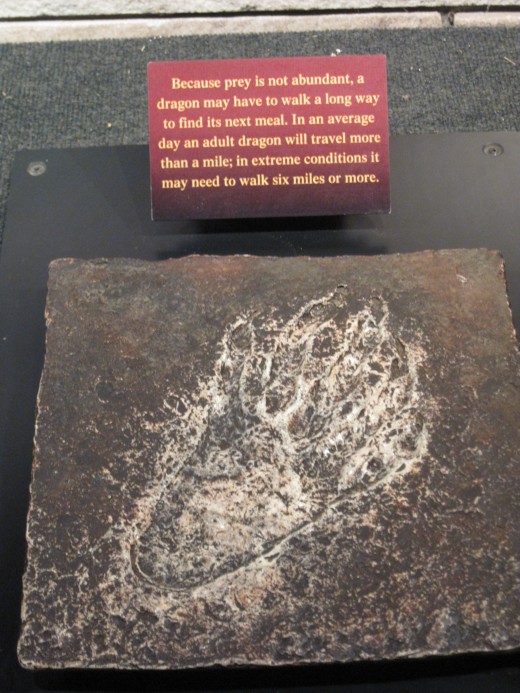

Thus, once attacked and bitten by Komodo Dragon, it is fairly certain that the victim will end up in the Komodo's stomach either immediately if the animal fails to get away or within a day or two after the poison from the bacteria in the saliva from the bite kills it. In the meantime the lumbering Komodo will track the victim using the keen sense of smell which it is endowed with through receptors on its tongue.

Scientists are unsure as to why Komodo Dragons support such a wide range of deadly bacteria in their mouths but some have theorized that their habit of eating dead and rotting animal carcases, basically road kill except that, due to the lack of motor vehicles in the Komodo's habitat, these animals died from other causes, is the source of this bacteria. This theory is strengthened by the fact that Komodo Dragons in zoos, who are fed a diet of fresh meat, have fewer amounts and varieties of deadly bacteria than their cousins in the wild.

New Theory Challenges Idea that Bacteria in Mouth of a Komodo Dragon Used to Kill Prey

The discussion above is the conventional wisdom regarding the hunting habits of the Komodo Dragon. Like everything else in science the explanation above is basically the theory developed by scientists to explain how Komodo Dragons hunt and kill their prey based upon available knowledge.

However, nothing is ever final in science as scientists are forever searching and attempting to learn more. When significant new facts come to light, new theories are developed to incorporate the new information.

This is what happened with our knowledge of Komodo Dragons with the publication on May 18, 2009 in the online publication of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America of an article entitled A central role for venom in predation by Varanus komodoensis (Komodo Dragon) and the extinct giant Varanus (Megalania) priscus by Bryan G. Fry of the Australian Venom Research Unit at the University of Melbourne, Stephen Wroe, Wouter Teeuwisse and a number of others.

Using MRI scans of the heads of Komodo Dragons and computer simulations of these skulls, the scientists made two big discoveries. First they discovered a large venom gland in the Komodo's head with ducts leading to the spaces between the teeth. While the venom is a rather mild variety and doesn't kill quickly, it does have an effect and serves to at least weaken the victim.

As to the bacteria in the Komodo's mouths, the types and amounts, while high and toxic, were discovered to be no different than the quantities and types of bacteria found in the mouths of other predators. While capable of causing severe or deadly infections in those attacked by a Komodo Dragon, this group concluded that the bacteria plays little or no role in the Komodo's killing capability.

The other major finding of the study was that the construction of the Komodo's skull was such that the force of its bite is not as hard or deep as previously thought especially when compared to the force of the bite of some of its crocodile cousins. However, what the Komodo appears to lack in bite force due to its skull design, it makes up for in its ability to hang on to a struggling prey.

Among the conclusions drawn from this study was the idea that Komodo's do not employ a bite and release strategy in which they wound a victim and then track it until it dies of infection and or blood loss before consuming it. Instead, the strategy seems to be to hide in ambush, grab a victim by surprise and hang on to it until a combination of the effect of the venom, shock and fatigue result in the prey giving up its struggle thereby allowing the Komodo to eat it.

Komodo Dragon at Woodland Park Zoo in Seattle, WA

In Science Theories Often Change

Scientific theories are attempts to explain how or why things work in our world. Scientists gather data and then use the data to explain things like how Komodo Dragons capture and kill their prey. All theories are considered valid only until new evidence shows the theory to be lacking in its ability to explain the phenomenon in its entirety.

The new theory above that resulted from work by Bryan Fry and others sheds new light on the hunting habits of the Komodo Dragon. The old theory made sense in many ways. In her 2004 book Bitten: True Medical Stories of Bites and Stings, author Pamela Nagemi describes some documented instances of humans being attacked and bitten by Komodo Dragons, both in the wild and in captivity, and escaping from the dragon. Most of those she cited died from blood loss or infection but some, who managed to get medical attention immediately, required massive doses of antibiotics in order to survive.

The discovery of massive amounts of deadly bacteria in the mouth of the dragons, recorded instances of humans being bitten and escaping, the Komodo's keen sense of smell and the fact that Komodo Dragon will consume dead animals it comes across makes it easy to theorize that Komodo Dragons could bite a victim and consume it even if the victim was able to escape its clutches and out run the slower moving Komodo.

Once Fry and his team discovered the venom gland it made sense to check the saliva in the mouth's of other predators to measure the quantity of deadly bacteria. The discovery that large quantities of deadly bacteria existed in other animals who did not rely on their victims dying from infection before consuming them, coupled with the fact that a bite from a Komodo also injected a venom into its victim gave scientists reason to look for a new theory to explain how Komodos obtained their food. This, plus the new knowledge about the construction of the Komodo's head along with new field reports describing the Komodo's tendency to ambush rather than chase its prey led to the new, and for now, more accurate theory of Komodo Dragon hunting habits.

Asexual Reproduction

Another new discovery about Komodo Dragons was reported in the December 21, 2006 edition of the weekly scientific journal Nature. This article described the recently discovered fact that female Komodo Dragons are capable of reproducing, without the help of a male Komodo Dragon, utilizing a process known as Parthenogenesis.

Parthenogenesis is a process in which an unfertilized egg within a female grows and develops despite the fact that it has not been fertilized by male sperm. Parthenogenesis is not uncommon in lower plant and animal species but, so far, only about 70 species of higher forms of life have been identified as having this capability. The Komodo Dragon is one of the more recent higher life forms to have been discovered to have this capability.

In Komodo Dragons, as with most other higher life forms that have

this capability, the offspring of this parthenogenesis process are

always female since they only receive X chromosomes from their mother.

Parthenogenesis differs from hermaphroditic reproduction in that the

creature giving birth has both male and female sex organs. Some worms

fall into this category and they are capable of producing both sperm

and eggs thereby fertilizing their eggs with their own sperm.

The

parthenogenesis is also not the same as cloning despite the fact that

all of the offspring's genetic material comes solely from the mother.

In the normal development of both sperm and eggs, each sperm and egg

gets only half of the genetic material of the producer of the sperm or

egg. The same is true of eggs that develop through parthenogenesis

which means that, while all of their genetic material is from the

mother, they are not a complete set of the mother's genes.

Komodo Dragons born as a result of parthenogenesis can mate and be impregnated by a male Komodo Dragon and give birth in normal fashion should a male Komodo Dragon enter their lives.

Parthenogenesis is a good news / bad news process. The good news is that the species can reproduce and multiply from a single female thereby by enhancing the chances of the species surviving. The bad news is that, in the absence of males, there is no way to add genetic diversity to the all female line that would be produced and whose genetic inheritance would be limited to the genes passed on from the original female. Just as breeding siblings with each other can result in a bad regressive gene becoming dominant so, too, can parthenogenesis result in a a bad regressive gene becoming dominant thereby weakening the genetic make-up of the line.

The general gist of the Nature article appears to be more concerned about this possible side effect, especially in zoos where male and female Komodo Dragons are generally not housed together in the same exhibit than it is about the discovery that Komodo Dragons are capable of parthenogenesis.

Komodo Dragons, because of their large size and remote habitat, have fascinated the public since their discovery by Westerners a century ago. Thanks to improved travel, the increasing number of zoos with Komodo Dragon exhibits and the ever increasing supply of nature films, the world has come to know and love Komodo Dragons. But, despite the increased exposure and familiarity by the general population, Komodo Dragons continue to surprise us with new discoveries about how they live.

- Komodo Dragons - Giant Lizards of Indonesia

September 19, 2009 Dragons are huge lizard-like creatures that breathe fire and used to terrorize the populace in tales of the Middle Ages. Dragons are, of course, mythical creatures that only existed in... - Komodo Dragon

- The Virtual Exploration Society: The Burden Expedition to Komodo Island

- Komodo Dragon - Zoos exhibiting Komodo Dragons

Komodo Dragons is an information rich resource on Komodo Dragons, the Komodo Islands and related reptiles. - Woodland Park Zoo presents The Komodo Dragon

Woodland Park Zoo Komodo Dragon Exhibit information - Woodland Park Zoo, Seattle WA

Woodland Park Zoo, Seattle, WA. Woodland Park Zoo is located in a 92-acre park located just minutes north of downtown Seattle. Open every day except Christmas. The zoo saves animals and their habitats through conservation leadership and engaging expe - Access : Parthenogenesis in Komodo dragons : Nature

Link to original article about parthenogenesis in Komodo Dragons. NOTE: link shows abstract only. A fee is required to access the full article. - BBC NEWS | UK | Magazine | How dangerous is a Komodo dragon?

A group of divers stranded on a remote island had to fight off a Komodo dragon. How dangerous are these creatures? - Komodo dragons kill prey with venom

Komodo dragons kill prey with venom, not oral bacteria, study suggests - Female Komodo Dragon Has Virgin Births | LiveScience

Maybe females could live without males, at least for Komodo dragons. These behemoths of the reptile world can produce babies without fertilization by a male.